|

| Tethydraco from Apple TV+'s Prehistoric Planet. |

If you grew up with BBC's landmark documentary Walking With Dinosaurs like I did, you might remember a scene from its last episode, "Death of a Dynasty", featuring a pterosaur called Quetzalcoatlus. It swoops down, skims for a fish from a small lake, and then lands by the shore. On the ground, its gangly form almost seems to limp, forecasting its coming extinction. Kenneth Branagh's narration solemnly informs us that this species of "delicate glider", with its 13-meter wingspan, are the last of their kind, pterosaurs having entered a mortal decline. As it flies away, scared off by a large crocodilian, we are told that the skies of the future will belong to the birds.

This was the popular image of pterosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous period for most of the 20th century: a dying breed, dwindling in numbers due to competition from modern birds. This was not a bad guess, per se, given what little information was available during much of that time. For decades, poor sampling limited our understanding of the evolution and life history of Late Cretaceous pterosaurs, and what representatives we did have were few, and mostly very large, seeming to imply that pterosaurs had abandoned the small flyer niches that birds dominate today.

Needless to say, a lot has changed in the last 20 years, and the image of the sad Quetzalcoatlus counting the days until its extinction is now a thing of the past. I was inspired by the impressive diversity of pterosaurs that I recently saw in Prehistoric Planet to write this post. The last of the pterosaurs were more diverse than we could have imagined a few decades ago, and it is my hope that this post will serve to paint you a picture of the world that they lived in.

The Lifestyles of Dragons

Were one to take popular culture at face value, one would get the impression that there were only a couple types of pterosaur (if you're lucky enough not to just get a bargain-bin pterodactyl for your trouble) and that they all did basically the same things. Typically these movie monsters only come in a "Rhamphorhynchus" variety or a "Pteranodon" variety, the latter often with teeth. It's also uncommon to see them exhibiting any behaviors other than skimming for fish or else picking up hapless prey with their feet like oversized ospreys. (The latter, incidentally, is a behavior which wasn't possible for any pterosaurs that we know of; their feet simply weren't built to grasp and bear a great deal of weight.)

|

| Pterosaurs resembling Rhamphorhynchus and Pteranodon as glimpsed in the webcomic "Homestuck" by Andrew Hussie. |

The Reign of the Azhdarchids

|

| Hatzegopteryx hunting the Romanian dinosaur Zalmoxes, by Mark Witton. Originally published in Naish & Witton 2017. Retrieved via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 4.0 |

In 1971, the world of paleontology was undergoing a rapid evolution. The science had, during the 1960s, just emerged from a lengthy hibernation that spanned the Great Depression and Second World War. Pioneering studies of the active, birdlike attributes of dinosaurs were just emerging onto the scene. That year, in Big Bend National Park, Texas, something new would likewise mark a leap forward in the study of pterosaurs.

Douglas A. Lawson, then only 23 or 24 years old, found something peculiar in the park's outcroppings of the Javelina Formation: the partial left wing of a truly massive pterosaur. First named Quetzalcoatlus northropi in 1975, after the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl and the aircraft designer John K. Northrop, this animal wasn't just remarkable for its truly immense size (with a wingspan estimated somewhere in the 11 meter range), but also for the manner of its fossilization. Up to that point, pterosaur fossils were known from marine deposits, such as the Blue Lias of England or the Solnhofen Limestone of Germany, but almost unheard of in terrestrial environments. Although an inland sea crawled up the American interior at the time Quetzalcoatlus lived, the Big Bend would still have been a great distance from the nearest shoreline. Clearly, something about the idea of pterosaurs exclusively being fish-eaters from marine and seaside habitats was amiss.

A related animal, Arambourgiania, had actually already been identified from a cervical vertebra found in the phosphate deposits of Jordan in the 1940s, and studied in the 1950s. Aside from its size, however, scientists of the time could glean little from this single bone. In the 1980s, the Soviet paleontologist Lev A. Nesov connected the dots with his description of another pterosaur from the Cretaceous of Uzbekistan. This animal, named Azhdarcho, a Persian word for "dragon", would in turn give its name to a family uniting all three of these genera, and even more in the years to come.

Most work on the Azhdarchidae, ultimately, would occur in the 21st century, with over a dozen new genera being named in the last 22 years. They were a cosmopolitan group, with specimens of azhdarchids, or of closely related animals, being found on every continent except Antarctica. Even that exception may be overturned eventually, as large pterosaur bones, albeit not verifiably azhdarchid in nature, are known from the latest Cretaceous of the Antarctic Peninsula. As a better picture of these animals has been painted by more complete fossils, we've started to understand a lot more about the shape and lifestyle of the azhdarchids. Although there have been several competing hypotheses, many researchers now believe that they lived a terrestrial lifestyle, stalking and opportunistically hunting small prey like storks or ground-dwelling hornbills of the family Bucorvidae do today. They certainly wouldn't have limped; in fact, they would have been pretty confident striders, moving upright on all fours.

Quetzalcoatlus, Arambourgiania, and Hatzegopteryx are all in approximately the same size range, with wingspans of 10 meters or more, and represented the largest flying animals ever known to have lived. They weren't all giants, however, and many species are much smaller. Their wide distribution during the Late Cretaceous suggests that they were an adaptable group which were at home in many different habitats. It has often been assumed that azhdarchids were long-distance gliders, and would have made cross-continental flights, but recent studies have cast some doubt on this. The fact that Romanian pterosaurs like Hatzegopteryx are so unique among the azhdarchids for their short necks and robust bodies implies that azhdarchid species had distinct regional differences, and likely were making long-distance voyages only rarely. Contrary to this hypothesis, there is a cervical vertebra from Tennessee which has been attributed to the otherwise Jordanian Arambourgiania, but I'm personally inclined to wait and see whether that actually pans out.

Azhdarchids had a long temporal range too, existing for at least 40 million years, and possibly quite a bit longer. Despite previous suggestions that they were in decline, their success only seems to have been abruptly halted by the end-Cretaceous extinction event. For a long time, three or four azhdarchid species were the only pterosaur fossils known from the last few million years of the Cretaceous, but this has also changed. In the 2010s, a remarkable fossil assemblage from Morocco gave us another piece of the puzzle and proved that azhdarchids weren't the only pterosaur group to still be around when the asteroid hit.

A Life at Sea

|

| Nyctosaurus, illustrated by Dmitry Bogdanov. This genus was extinct by the Maastrichtian, but the relatively complete fossils we have for Nyctosaurus may help us to reconstruct its close relatives. Retrieved via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0 |

The Bird Quandary

|

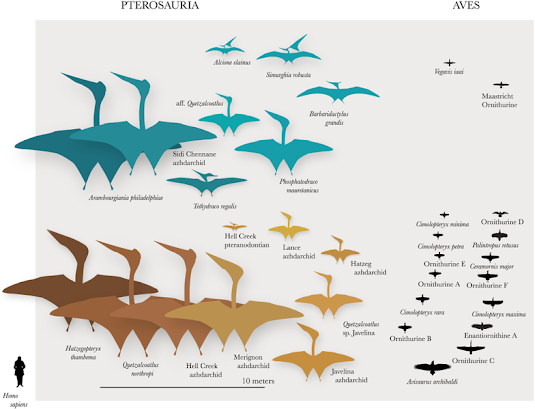

| A figure from Longrich et al. (2018) comparing body size in marine (blue) and terrestrial (brown) Maastrichtian pterosaurs and birds. Retrieved via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 4.0 |

- The fact that Maastrichtian pterosaurs were more taxonomically diverse than previously assumed.

- New evidence of prenatal development suggesting widespread precociality in pterosaurs, which implies that the young filled different niches than the adults.

The Age of Pterosaurs

Our knowledge of pterosaurs is growing by leaps and bounds at a rate we've never seen before. This doesn't just go for the very last pterosaurs either; it goes for the earliest pterosaurs in the Triassic, the period in the Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous when they flourished, and everywhere in between. Pterosaurs first became known to science in the late 18th century, but the vast majority of all published studies about them have come out since the year 2000. Entirely new families are being identified, gaps are being filled in, and the trajectory still seems to be upward from here.

We live in an age of pterosaurs, but more generally, we also live in an age of paleontology. If the 1960s - 1980s were a renaissance, then I don't know what to call the period we're in now, where the field has never been more vibrant. What I do know is that this blog post is probably going to be outdated in just a couple of years, and I couldn't be happier about it.

|

| Barbaridactylus from Apple TV+'s Prehistoric Planet. |

Thanks for reading. Our next post will be about sauropod dinosaurs, a group which I've so far neglected to mention very much. After that, who knows? The sky is the limit...

Sources:

- Andres, Brian and Wann Langston, Jr. (2021) "Morphology and taxonomy of Quetzalcoatlus Lawson 1975 (Pterodactyloidea: Azhdarchoidea)." Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 41.1: 46-202. DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2021.1907587

- Bennett, S. Christopher. (1995) "A statistical study of Rhamphorhynchus from the Solnhofen Limestone of Germany: Year-classes of a single large species." Journal of Paleontology 69.3: 569 - 580. DOI: 10.1017/S0022336000034946

- Bestwick, Jordan, David M. Unwin, Richard J. Butler, Donald M. Henderson, and Mark A. Purnell. (2018) "Pterosaur dietary hypotheses: a review of ideas and approaches." Biological Reviews 2018.93: 2021 - 2048. DOI: 10.1111/brv.12431

- Butler, Richard J., Paul M. Barrett, Stephen Nowbath, and Paul Upchurch. (2009) "Estimating the effects of sampling biases on pterosaur diversity patterns: implications for hypotheses of bird/pterosaur competitive replacement." Paleobiology 35.3: 432 - 446. DOI: 10.1666/0094-8373-35.3.432

- Kellner, Alexander W. A., Taissa Rodrigues, Fabiana R. Costa, Luiz C. Weinschütz, Rodrigo G. Figueiredo, Geovane A. De Souza, Arthur S. Brum, Lúcia H. S. Eleutério, Carsten W. Mueller, and Julian M. Sayão. (2019) "Pterodactyloid pterosaur bones from Cretaceous deposits of the Antarctic Peninsula." Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 91.2: e20191300. DOI: 10.1590/0001-3765201920191300

- Longrich, Nicholas R., David M. Martill, and Brian Andres. (2018) "Late Maastrichtian pterosaurs from North Africa and mass extinction of Pterosauria at the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary." PLoS Biology 16.3: e2001663. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2001663

- Martin-Silverstone, Elizabeth, Mark P. Witton, Victoria M. Arbour, and Philip J. Currie. (2016) "A small azhdarchoid pterosaur from the latest Cretaceous, the age of flying giants." Royal Society Open Science 3:160333. DOI: 10.1098/rsos.160333

- Naish, Darren, and Mark P. Witton. (2017) "Neck biomechanics indicate that giant Transylvanian azhdarchid pterosaurs were short-necked arch predators." PeerJ 5:e2908. DOI: 10.7717/peerj.2908

- Naish, Darren, Mark P. Witton, and Elizabeth Martin-Silverstone. (2021) "Powered flight in hatchling pterosaurs: evidence from wing form and bone strength." Science Reports 11.13130. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-021-92499-z

- Smith, Roy E., Anusuya Chinsamy, David M. Unwin, Nizar Ibrahim, Samir Zouhri, and David M. Martill. (2021) "Small, immature pterosaurs from the Cretaceous of Africa: implications for taphonomic bias and palaeocommunity structure in flying reptiles." Cretaceous Research 130:105061. DOI: 10.1016/j.cretres.2021.105061

- Unwin, David Michael and D. Charles Deeming. (2019) "Prenatal development in pterosaurs and its implications for their postnatal locomotory ability." Proceedings of the Royal Society B 286:20190409. DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2019.0409

- Witton, Mark P. and Darren Naish. (2015) "Azhdarchid pterosaurs: water-trawling pelican mimics or 'terrestrial stalkers'?" Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 60.3: 651 - 660. DOI: 10.4202/app.00005.2013